The Flight I’ll Never Forget: Transformation through Growth Mindset

Not many people can say they’ve been transformed on an airplane. Even fewer could say they’ve been transformed during a midnight flight to San José.

Slumped in the crowded plane among the other weary travelers 12 years ago, however, I was.

On the surface, this flight wasn’t particularly noteworthy. I was headed to California to learn about a new project I’d be working on. During the flight, I was planning to read a couple of articles to prepare for workshops the next day.

As I read the materials, suddenly the tears started. They came from a feeling of deep regret and an epiphany long overdue.

The regret: I wanted a do-over with the students whom I may have harmed through my ignorance when I taught middle school before joining the Dana Center.

The epiphany: I finally understood why I didn’t go to college until I was 26.

By the time my flight landed around 1:30 a.m., my transformation had begun. I had been introduced to the concept of learning mindsets.

Words Matter: Moving from Fixed to Growth Mindsets

Many of you who teach will recognize this exchange:

Student: “Miss! I’m not smart enough to do this.”

My response as the teacher: “Of course you are!”

Sounds benign enough, but responses like the ones I used to give reinforce the mindset that intelligence is a fixed, unchangeable attribute.

Today, after all I’ve learned about mindsets, attributions, and other ideas from educational psychology, I would respond to that student much differently.

It would sound more like: “I’m glad you’re feeling challenged because that’s how we learn. It’s okay to feel frustrated. What strategies have you tried so far?”

People with a growth mindset—the understanding that anyone can get better at anything with consistent and effective effort—exhibit greater motivation, persistence, and self-regulation in school.

People with a fixed mindset believe (or have been told) that they have only a certain amount of intelligence, and there is nothing they can do to change it.

People with a fixed mindset believe (or have been told) that they have only a certain amount of intelligence, and there is nothing they can do to change it.

Mindset matters—especially for students who have historically been marginalized by low expectations, systemic racism, and the lie that only some people can succeed at mathematics.

Folks with a fixed mindset are more likely to give up in the face of challenges. It’s the thinking of, what’s the point of trying if you’re just not smart enough to succeed?

Because of this inaccurate mental model, many students (and instructors) also tend to turn down valuable learning opportunities and worry that struggling—or failing—means that they are simply not smart.

I used to be one of those people.

Change Starts from Within

Once I started to learn about mindsets, nothing was ever quite the same.

The semester after that fateful plane ride, I began graduate school in The University of Texas at Austin’s department of Curriculum and Instruction. While I was thrilled to start this program, what I really wanted to learn was the psychological factors I had begun to obsessively read about, of which growth mindset was only one.

Each semester, I approached my professors to seek permission to deviate a bit from the syllabus. I will be forever grateful that each allowed me to pursue my interests, as long as I could connect it to the course topic.

Looking back at my experience in graduate school, where I was confident in my abilities and even took on extra work to pursue the knowledge I was passionate about, I think about my decision not to begin college until my late 20s.

I had never wanted to go to college because I didn’t believe that I could succeed. I didn’t believe that I belonged in college because I had rarely felt a sense of belonging in school. And I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. This trio of mindsets—capability, belonging, and purpose—is at the heart of many important choices that students make daily.

But at 26, I was finally ready. I wanted to learn because I knew that I could.

I had survived for five years in low-wage jobs without access to credit. In each successive job after high school—grocery store cashier, insurance company file clerk, U.S. Postal Service letter carrier—I was given additional responsibilities and opportunities to learn new skills. My supervisors saw something in me, and, at the post office, I was serving on a committee that sought to increase the number and diversity of staff serving in supervisory roles.

I was expected to submit my application to enter the supervisor-in-training program, but suddenly I was unsure if that was what I really wanted to do. The next week, as I was walking toward my final mail delivery of the day, it struck me as if by lightning: I would be a teacher.

I sold my home, quit my job, and applied to college.

Spreading the Message: Academic Youth Development

In grad school, the more I learned about the psychological and learning science concepts that could hinder—or help—student achievement, the more ideas I had for how these concepts could be better connected to mathematics instruction.

The Dana Center is known for translating research into practice, and I was beginning to understand concrete ways that I could contribute to those efforts from the practitioner’s perspective.

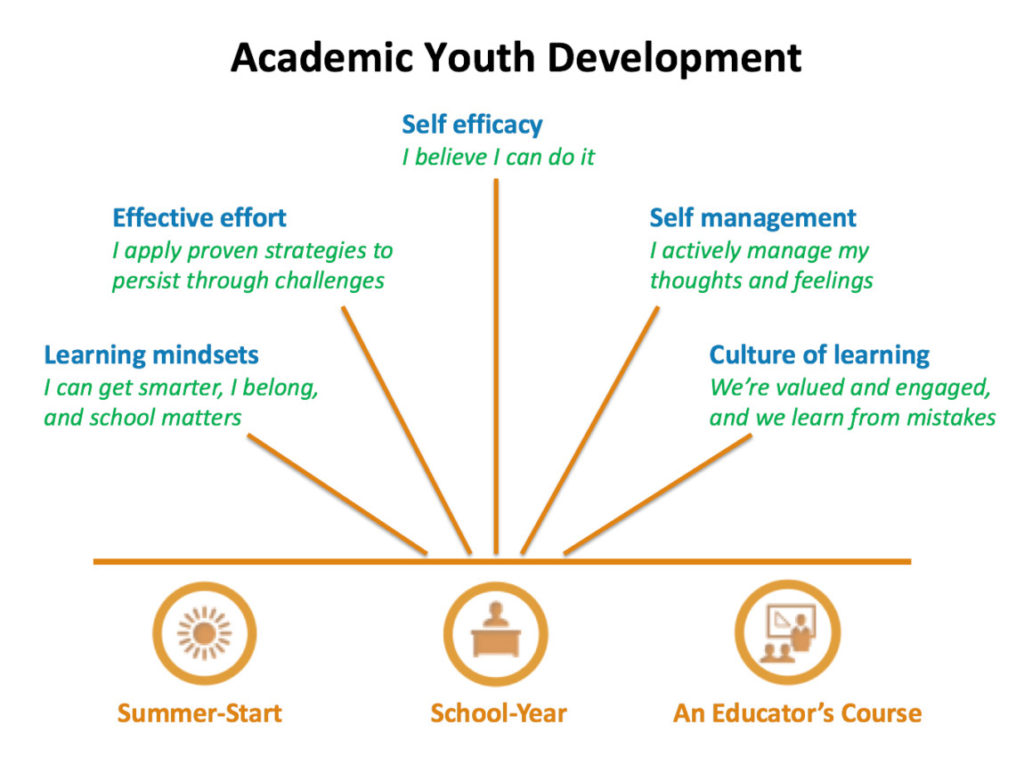

Not long after that San José trip, I was assigned to the authoring team for the program known today as Summer-Start Academic Youth Development. Created by the Dana Center—in collaboration with education publisher Agile Mind and leading psychologists and learning scientists—AYD incorporates key ideas and academic strategies from psychology and the learning sciences into a three-week summer experience for rising Algebra I students. It introduces them to growth mindset, belonging, self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning—as well as specific strategies for promoting a classroom culture of mutual accountability in which students didn’t have to choose between “being smart” or “being cool.”

Designing and building a summer program from scratch while attending graduate school and studying topics outside my primary wheelhouse wasn’t easy. Once I finished that degree and published my thesis, I knew what I had learned would be useful to other math teachers.

I began presenting to Agile Mind teachers, then expanded to giving talks at state, regional, and national conferences. Eventually, I was tapped not just to author but to lead the Dana Center’s Academic Youth Development work, which now includes three programs, each infused with the latest and most relevant psychological and learning sciences research.

My journey to this point would not have been possible if my mindset had stayed fixed. With AYD programs reaching thousands of students nationwide, and my work speaking around the country to K–16 educators, I hope students and fellow educators learn about and embrace growth mindsets. Most of all, I hope they begin to see that they, too, can transform how they approach their learning and their lives.

Learn more about learning mindsets…

Mindset Scholars Network

The Mindset Scholars Network promotes scientific understanding of learning mindsets by conducting original research, scientific leadership, and outreach. The network is a reliable and authoritative resource for understanding learning mindsets, including mindsets related to capability, belonging, purpose, and relevance.

Learning and the Adolescent Mind

The Dana Center and education publisher Agile Mind collaborated to launch Learning and the Adolescent Mind, which features examples and resources explaining key concepts from the learning sciences as they apply to learning mathematics.

Academic Tenacity

In 2014 the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation published Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills That Promote Long-Term Learning, a free report that details concepts and strategies to help students attain academic tenacity—which is grounded in psychological concepts including mindsets and goals, sense of belonging, and self-regulation.

Social and Emotional Learning and Mathematics

Inside Mathematics has fantastic information about the connections among the mathematical practices and social and emotional learning competencies, as well as supports for integrating them in your classroom instruction.

About the Author

Lisa Brown

My favorite 11th-grade teacher Elizabeth Aston-Sullivan insisted I take a fourth year of math in high school. She saw something in me that took me nine years to see for myself. Once I became an educator, amazing mentors helped and encouraged me—including my students, whose actions, emotions, and beliefs shaped my teaching.

Get in Touch

We collaborate with state districts and teachers to develop innovative curricula, resources, and professional development.